The Aga Khan on the Cosmopolitan Ethic and the Unity of the Human Race

Articulating Ismaili spiritual ethics and our ultimate moral responsibility to the whole of humanity

“O mankind! Be careful of your duty to your Lord, who created you from a single soul

and from it created its mate and from the twain hath spread abroad

a multitude of men and women.”

« Qur’an 4:1 »

Pluralism and the Cosmopolitan Ethic

(Excerpted from Faith and Ethics: The Vision of the Ismaili Imamat, by M. Ali Lakhani, Chapter 5, pp. 87-94)

Pluralism and the Principle of Inclusiveness

As cosmopolitanism is the ethic of harmonious and equitable coexistence, so pluralism is the ethic of the dignified dialogue with diversity in order to attain harmony and equity. Cosmopolitanism is based on the principle of our common humanity…. Pluralism, founded on the principle of inclusiveness, is based on a respect for human individuality and, concomitantly, on a respect for the richness of diversity and theophany as an aspect of wholeness.

The principle of inclusiveness can be seen as having ‘metaphysical’ roots: its foundation is the unity that underlies multiplicity, and it is reflected in the Quranic verse, cited above, about the intrinsic oneness of mankind, created from ‘a single soul’ (Q 4:1). Underlining its importance, the Aga Khan has described this verse as a ‘touchstone’, whose message he has ‘long treasured and sought to apply’, one he regards as ‘a spiritual legacy which distinguishes the human race from all other forms of life’.1 Any universal ethos requires a universal foundation, and it is on this conception of a unified humanity as an aspect of all-encompassing reality that the Imam has chosen to underpin the Imamat’s work in constructing a bridge between faith and ethics. This ideal underlies the broad values mentioned in the Ismaili Constitution, ‘of unity, brotherhood, justice, tolerance and goodwill’,2 and the Imamat’s emphasis on the humanistic value of tolerance – a quality which the Aga Khan has described as ‘a sacred religious imperative’3 – a quality of ‘the human spirit, guided and supported by the Divine Will’.4

Pluralism is a vital part of Islam. The Quran’s cosmopolitan and inclusive message – which teaches man to have faith in all-encompassing reality and to live in accord with its sacred ethical imperatives – is inherently pluralistic. The Muslim scripture is not exclusivist. On the contrary, it contains a confirmatory and universal message (Q 3:48),5 affirming the principles expressed in what are considered the revelations that preceded it (Q 10:37), received not only through those regarded as the prophets of the Abrahamic tradition, but also through the myriad messengers considered to be sent by God throughout history to humanity’s many diverse communities (Q 10:47, 16:36, 40:78)….6

[. . .] So also, in considering one’s fitness for salvation, the scripture does not rank people as superior or inferior according to affiliation, but considers their souls, intentions and deeds. Thus, the only criteria for salvation in Islam are, firstly, faith in the transcendent, originating, underlying and sustaining reality which binds us all, and to which we are ultimately accountable, and secondly, the expression of that faith as conforming virtue (Q 2:62, 2:111–12, 4:122, 4:124–5)….7

[. . .] In the Ismaili view, just as faith entails virtue, so the principle of inclusiveness mandates ‘ethical imperatives’, promoting harmony and equity as the ethos necessary for an equitable social order. Pluralism thereby reflects the metaphysics of participation, in which humanity – unique and distinct in its diversity, but intrinsically one – possesses an underlying harmony and a dynamic participatory wholeness that is essential to its ethical life. A healthy sense of community and the dignity of the individual man and woman are essential to its expression.

The Quranic principle of inclusiveness is the basis for its ethical imperatives. Metaphysically, the diversity of creation reflects the non-repetition of theophany, which requires our acceptance of its ever-changing variety, and therefore of the Other. At the same time, it requires us to look beyond the ‘representation’ of the changing outer world to the abiding and underlying presence that is the inner source and matrix of all change. The Other and the self are both aspects of the one and only reality. This inclusive approach is the foundation of human ethical conduct and social order, entailing a participatory engagement of human intelligence and effort.

The Aga Khan has emphasised ‘an understanding of the Holy Quran as a message that encompasses the entirety of human existence and effort’, including its ethics:8

It is concerned with the salvation of the soul, but commensurately also with the ethical imperatives which sustain an equitable social order. The Quran’s is an inclusive vision of society that gives primacy to nobility of conduct. It speaks of differences of language and colour as a Divine sign of mercy and a portent for people of knowledge to reflect upon.9

In this inclusive scheme, all of humankind is enjoined to vie with one another in good works (Q 5:48) – in other words, to engage in acts of creative virtue through an ethic of inclusiveness and compassion, harmony and equity, tolerance and generosity, respectful of human dignity. These virtues, universal in their appeal, and founded on an integral vision that sustains their ethical imperatives, inform the cosmopolitan ethic of the Ismaili Imam.

A Cosmopolitan Ethic

Flowing from the idea that humanity is one is the idea that it must be subject to a common set of ethical norms. Because its spiritual foundations are based on a shared understanding of the common human bond, moral behaviour cannot be limited to religious prescriptions. Its sources lie in ontology, not in the confines of exoteric discourse, and therefore what binds humanity together cannot be effectively promoted through narrow theological frameworks or polemically-driven religious ideology. Each religion expresses general norms in particular ways. They each express universal principles through forms which can be narrowly construed, or use theological idioms that are not necessarily understood or accepted outside the contexts of their adherents, and which, due to the proselytism inherent in theological discourse, can promote divisions among groups rather than help to bridge differences. A further problem arises in respect of those who see themselves as largely non-religious. This is especially significant in the modern age where secularist cynicism poses an added threat to religious formulations of morality. For all these reasons, there is a need for prudence in addressing ethical formulations in overtly religious or theological language.

For the Aga Khan, cosmopolitanism is a way of promoting faith-based values outside the narrow – and to some, threatening or divisive – framework of religious discourse. Thus he has remarked: ‘I have serious doubts about the ecumenical discourse, and about what it can reach, but I do not have any doubts about cosmopolitan ethics.’10 Elsewhere he observed:

In recent decades, inter-faith dialogue has been occurring in numerous countries. Unfortunately, every time the word ‘faith’ is used in such a context, there is an inherent supposition that lurking at the side is the issue of proselytisation. But faith, after all, is only one aspect of human society. Therefore, we must approach this issue today within the dimension of civilisations learning about each other, and speaking to each other, and not exclusively through the more narrow focus of inter-faith dialectic.11

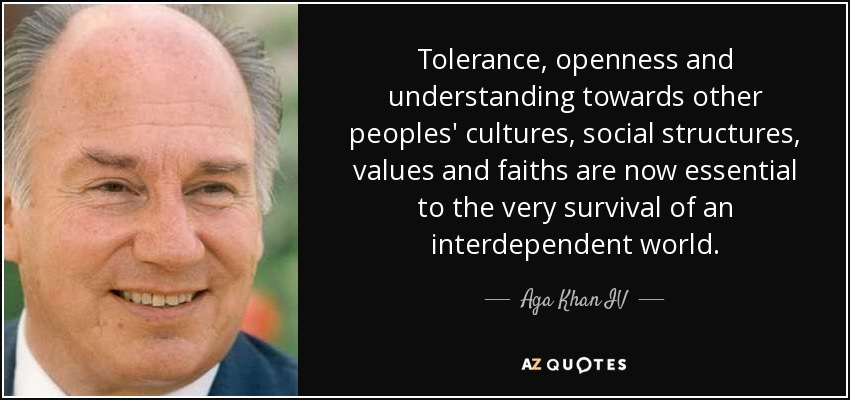

Since ‘there will always be limits in inter-religious dialogue’, the Aga Khan’s approach is to engage groups on the basis of unifying humanistic principles.12 Recognising that ‘a cosmopolitan ethic is one that resonates with the world’s great ethical and religious traditions’, his strategy has been to promote ethical values principally outside the context of theological articulations or interfaith ecumenism.13 Instead, he advocates an inclusive approach that respects diversity, through a cosmopolitan ethic ‘shared across divisions of class, race, language, faith and geography’,14 that ‘accepts our ultimate moral responsibility to the whole of humanity, rather than absolutising a presumably exceptional part’.15 He views the cosmopolitan ethic as one benefitting ‘the whole of humanity’, ‘where the unity of the human race becomes an ethical purpose for all faiths’.16

Cosmopolitanism, while it opposes provincialism, respects the diversity of plural identities, traditions and cultures. Accompanied by ‘a readiness to accept the complexity of human society’, it places value on the unique gifts of creation, in individual expression or in the particularity of traditions, and it appreciates diverse cultural values as an aspect of the heritage and identity of communities.17 In practice, therefore, the cosmopolitan ethic implies ‘a readiness to participate in a true dialogue with diversity’.18 It is based on a healthy pluralism, ‘respecting both what we have in common and what makes us different’.19

[. . . ]Despite the Aga Khan’s disinclination towards interfaith discourses because of their potential to be divisive, he underscores that the ethical bond between human beings has deep spiritual roots. Ethical integrity derives from faith in an integrated reality, without which – according to the Karamazovian dictum – the danger is that ‘everything is permitted’. The Aga Khan has often articulated this ethical bond, acknowledging that his own ‘commitment to the principle of tolerance is based on spiritual understandings which are rooted in ancient teachings’.20 Note, for instance, the following passage, where he is speaking of the cosmopolitan ethic:

It will not surprise you to have me say that such an ethic can grow with enormous power out of the spiritual dimensions of our lives. In acknowledging the immensity of the Divine, we will also come to acknowledge our human limitations, the incomplete nature of human understanding.21

Ismailis believe that it is in acknowledging the infinite greatness of God (‘the immensity of the Divine’) that diverse human groups can recognise their own common humanity and also that each person can recognise his or her own individual limitations. It is in humility and wholeness that one can discover the basis for mutual interdependence, and can recognise the value of the ethic of cooperation, harmony, generosity, fairness and caring for the Other. On this view, each person becomes spiritually committed to the Other in the quest for the common good. Citing as examples the Quranic principle of the unity of humankind, and Imam Ali’s integration of knowledge with tolerance, the Aga Khan has stated:

The spiritual roots of tolerance include, it seems to me, a respect for individual conscience - seen as a Gift of God – as well as a posture of religious humility before the Divine. It is by accepting our human limits that we can come to see the Other as a fellow seeker of truth and to find common ground in our common quest.22

The ‘common quest’ – the goal of the cosmopolitan ethic – is for the just society that constitutes the common good. This is the underlying basis for social order, the balancing of freedom and responsibility conducive to respecting human dignity and social justice, and to the attainment of the good life to which all communities aspire.

[. . . ] A just social order is founded on the common good of a better quality of life for all, and filled with opportunity and hope for the future. The Aga Khan’s appeal, in the end, is to promote those shared values that profoundly connect us, and which ultimately enable us to overcome our outer differences.

(Note: The numbering in the annotation above differs from the original text)

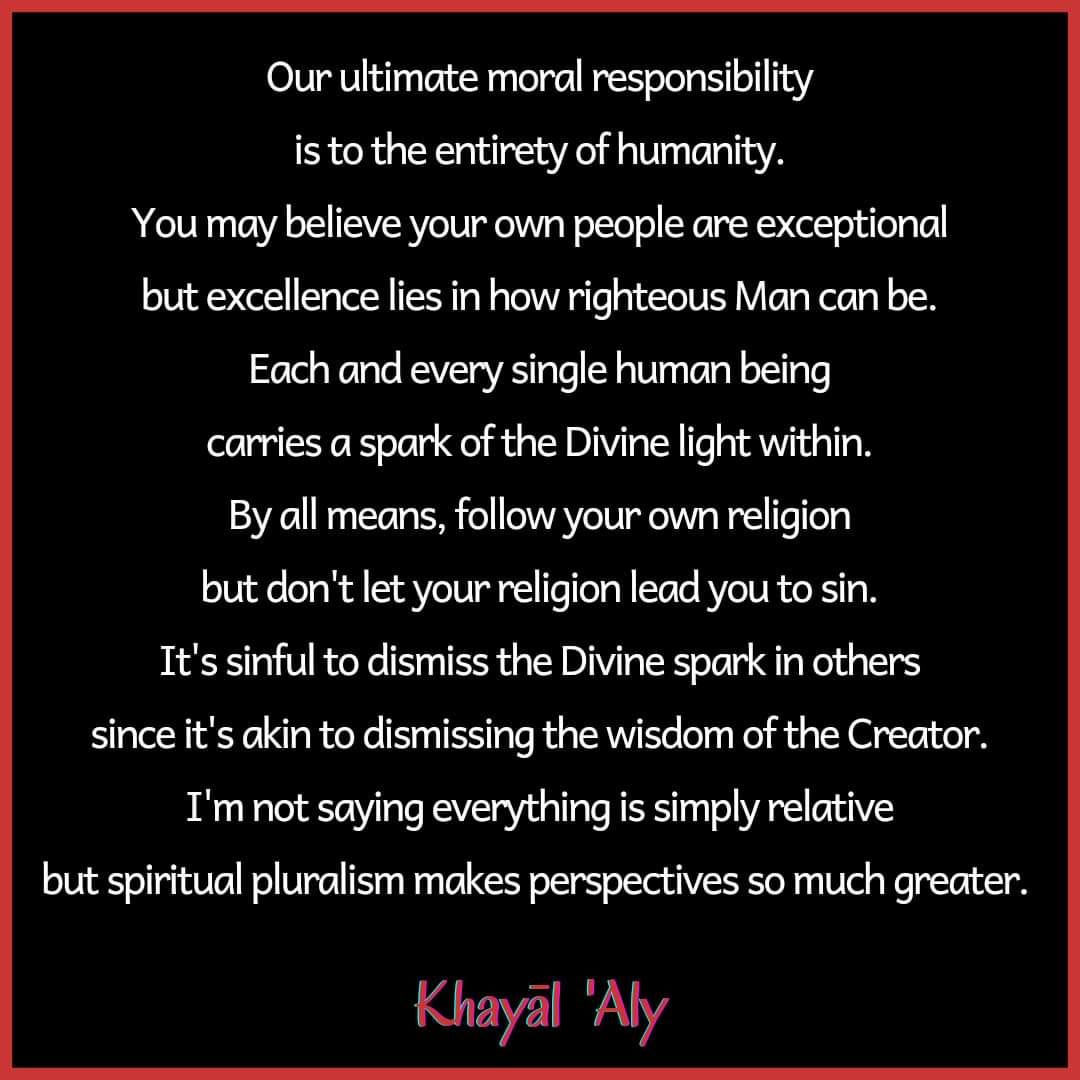

“Our Ultimate Moral Responsibility”: A Poem on Spiritual Pluralism by Khayal ‘Aly

The poem, “Our Ultimate Moral Responsibility”, as can be immediately seen in its title and opening line, was inspired while reading the above material from Faith and Ethics: The Vision of the Ismaili Imamat, particularly the section on “A Cosmopolitan Ethic” where the author, M. Ali Lakhani, quoting the 49th Ismaili Imam, Mawlana Shah Karim al-Husayni Hazir Imam⁽ˢ⁾, explains how Aga Khan IV advocates an inclusive approach that “accepts our ultimate moral responsibility to the whole of humanity….” After the initial inspiration initiated the creative process, further inspiration was drawn from Mawlana Hazir Imam’s predecessor and grandfather, Mawlana Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III, who, in his memoirs, emphasized the importance of the “spark of the Divine Light” which is within all human beings and which, as the 48th Imam implores, ought to be fully developed through spiritual acts of worship, like intense prayer and meditation, but also through righteous acts of mutual aid and peace, one to another, irrespective of one’s faith or the lack thereof.

khayal.aly@gmail.com

Follow on Instagram

@khayal.aly

@ismaili.poetry

@khana_yi_khayr

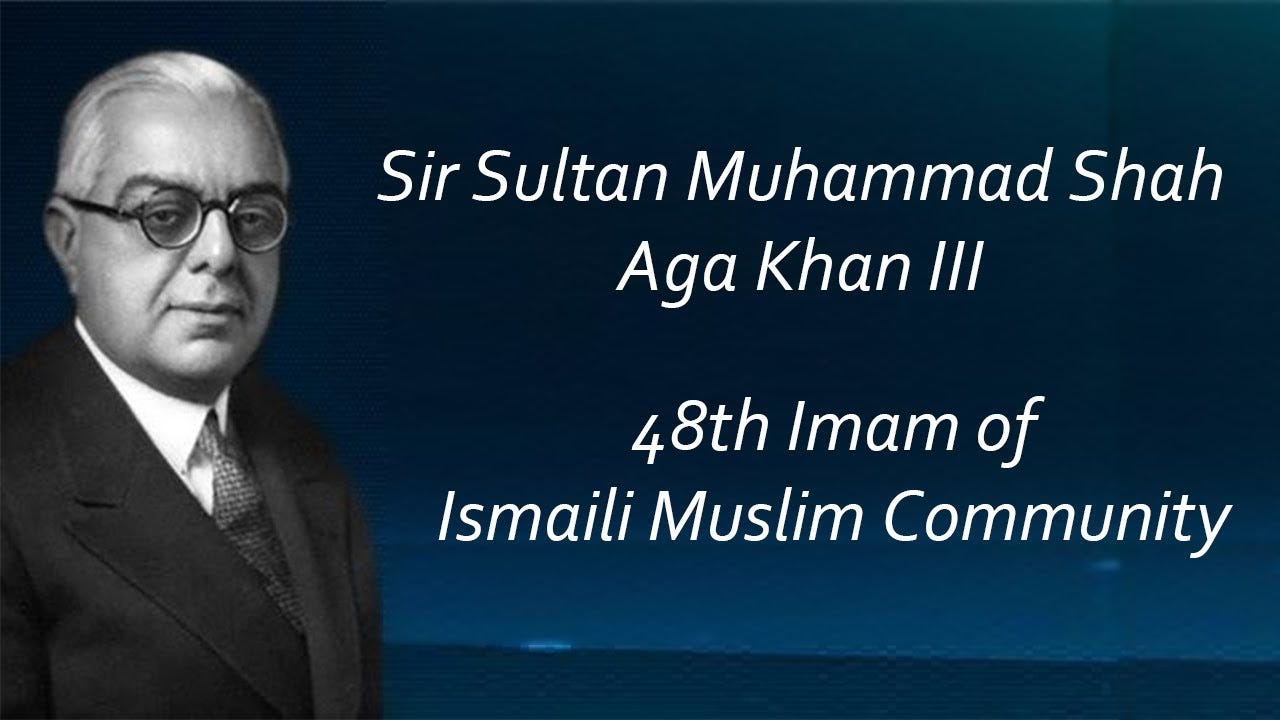

Aga Khan III: All Carry in Them a Spark of the Divine Light

(Excerpted from The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time, by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III, pp. 176-77, 334).

“Let us then study the duties of man, as the great majority interpret them, according to the verses of the Koran and the Traditions of the Prophet…. The healthy human body is the temple in which the flame of the Holy Spirit burns…. Prayer is a daily necessity, a direct communication of the spark with the universal flame...slander, and thinking evil of one’s neighbour are specifically and severely condemned. All men, rich and poor, must aid one another materially and personally. The rules vary in detail, but they all maintain the principle of universal mutual aid in the Muslim fraternity. This fraternity is absolute and comprises men of all colours and of all races: black, white, yellow, tawny; all are the sons of Adam in the flesh and all carry in them a spark of the Divine Light. Everyone should strive his best to see that this spark be not extinguished but rather developed to that full ‘Companionship-on-High’ which was the vision expressed in the last words of the Prophet on his deathbed, the vision of that blessed state which he saw clearly awaiting him” (Memoirs, 176).

“Wars are condemned. Peace ought to be universal. Islam means peace, God’s peace with man and the peace of men one to another” (Memoirs, 177).

“Every individual, every molecule, every atom has its own spiritual relationship with the All-Powerful Soul of God. But men and women, being more highly developed, are immensely more advanced than the infinite number of other beings known to us” (Memoirs, 177).

“I can only say to everyone who reads this book of mine that it is my profound conviction that man must never ignore and leave untended and undeveloped that spark of the Divine which is in him. The way to personal fulfilment, to individual reconciliation with the Universe that is about us, is comparatively easy for anyone who firmly and sincerely believes, as I do, that Divine Grace has given man in his own heart the possibilities of illumination and of union with Reality. It is, however, far more important to attempt to offer some hope of spiritual sustenance to those many who, in this age in which the capacity of faith is non-existent in the majority, long for something beyond themselves, even if it seems second-best. For them there is the possibility of finding strength of the spirit, comfort, and happiness in contemplation of the infinite variety and beauty of the Universe” (Memoirs, 334).

Additional Inspirational Words of Wisdom from The Memoirs of Aga Khan on Respect for the Beliefs of Others' and Compassion for All

(Excerpted from The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time, by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III, pp. 16-19)

“My three tutors gave me the key to knowledge, and for that I have always been profoundly grateful to Mr. Gallagher, Mr. Lawrence, and Mr. Kenny. Of them I can say nothing but good. But, alas, of the man responsible for my education in Arabic and Persian and in all matters Islamic I have nothing but bad to say. He was extremely learned, a profound scholar, with a deep and extensive knowledge of Arabic literature and of lslamic history, but all his learning had not widened his mind or warmed his heart. He was a bigoted sectarian, and in spite of his vast reading his mind was one of the darkest and narrowest that I have ever encountered. If Islam had indeed been the thing he taught then surely God had sent Mohammed not to be a blessing for all mankind but a curse…. It was saddening and in a sense frightening to listen to him talk. He gave one the feeling that God had created men solely to send them to hell and eternal damnation” (Memoirs, 16-17).

“[. . .] In England I have had many friends all my life among the Quakers, and I am aware of a tranquil sense of mental and spiritual communion with them, for our mutual respect for each other’s beliefs — mine for their Quakerism, theirs for my Islamic faith — is absolute. The vast majority of Muslim believers all over the world are charitable and gently disposed to those who hold other faiths, and they pray for divine forgiveness and compassion for all. There developed, however, in Iran and Iraq a school of doctors of religious law whose outlook and temper —intolerance, bigotry, and spiritual aggressiveness — resembled my old teacher’s, and in my travels about the world I have met too many of their kind — Christian, Muslim, and Jew — who ardently and ostentatiously sing the praises of the Lord, and yet are eager to send to hell and eternal damnation all except those who hold precisely their own set of opinions. For many years, I must confess, this is a sort of person I have sought to avoid” (Memoirs, 16-18).

“It was strange and it was out of place that a boy, whose home and upbringing were such as mine in India, should have been submitted in adolescence to a course of this narrow and formalist Islamic indoctrination. For my early environment was one of the widest tolerance; there was in our home never any prejudice against Hindus or Hinduism….” (Memoirs, 18).

“In addition, my mother was herself a genuine mystic in the Muslim tradition (as were most of her closest companions); and she habitually spent a great deal of time in prayer for spiritual enlightenment and for union with God. In such a spirit there was no room for bigotry. Like many other mystics my mother had a profound poetic understanding. I have in something near ecstasy heard her read perhaps some verses by Roumi or Hafiz, with their exquisite analogies between man’s beatific vision of the Divine and the temporal beauty and colours of flowers, the music and the magic of the night, and the transient splendours of the Persian dawn. Then I would have to go back to my gloomy treadmill and hear my tutor cursing and railing as was his habit. Since he was a Shia of the narrowest outlook he concentrated his most ferocious hatred not on non-Muslims, not even on those who persecuted the Prophet, but on the caliphs and companions of the Prophet…. This form of Shiaism attains its climax during the month of Moharram with its lamentations and its dreadful cursings. Reaction against its hatred, intolerance, and bigotry has, I know, coloured my whole life, and I have found my answer in the simple prayer that God in His infinite mercy will forgive the sins of all Muslims, the slayer and the slain, and that all may be reconciled in Heaven in a final total absolution.

And I further pray that all who truly and sincerely believe in God, be they Christian, Jew, Buddhist, or Brahmin, who strive to do good and avoid evil, who are gentle and kind, will be joined in Heaven and be granted final pardon and peace. I could wish that all of other creeds would have this same charity towards Muslims….” (Memoirs, 18-19).

Recommended Reading

Title: “Divine Diversity: The Aga Khan’s Vision of Pluralism”

Author: Khalil Andani

Source: Journal of Islamic and Muslim Studies , Vol. 4, No. 1 (May 2019), pp. 1-42

Abstract: This article analyzes the Aga Khan’s discourse on pluralism and cosmopolitan ethics, arguing that these ideals are rooted in and expressive of his Muslim theological vision and constitute his interpretation of Islam. The Aga Khan is the forty-ninth hereditary Imam of the Nizari Ismaili Muslims and a public Muslim intellectual. Whereas many theorists’ approaches to pluralism are premised on the religious diversity of America, the Aga Khan pragmatically situates pluralism as a prerequisite for humanitarian development in a global context and as an antidote to dangers posed by both political tribalism and globalism. In common with the scholar of religion Diana Eck, the Aga Khan defines pluralism as a personal and civic orientation toward human diversity that actively embraces difference while also emphasizing commonality without overriding differences. At the same time, he presents pluralism as a divine imperative for humans in responding to God-given diversity and attaining self-knowledge. The theological underpinnings of the Aga Khan’s pluralistic vision are the integration of Faith (dīn) and World (dunyā) and a theology of “mono-realism” (waḥdat al-wujūd) stressing God’s continuous manifestation through diversity. Certain dimensions of this pluralism are rooted in the pre-modern Ismaili theological heritage. The Aga Khan also presents a concept of cosmopolitan ethics as a necessary concomitant of applied pluralism. Rejecting both moral relativism and a hegemonic universalism, the Aga Khan defines cosmopolitan ethics as universal virtue ethics informed by multiple religious traditions that can also accommodate a pluralism of values in local contexts. The Aga Khan theologically roots cosmopolitan ethics in the Qur’ānic vision of humankind as created from a single soul (Q 4:1).

Title: “Pluralism and the Qur’an”

Author: Reza Shah-Kazemi

Source: Speech at Milad al-Nabi Celebrations, Atlanta and San Francisco, USA, 2007

Abstract: Dr. Shah-Kazemi opens this article with the narration of Prophet Muhammad’s invitation to a group of Christians in 631 CE to perform their rites in his own mosque. This remarkable event was reported by Ibn Ishaq and others. As Dr Shah-Kazemi says “one observes here a perfect example of how disagreement on the plane of dogma can co-exist with deep respect on the superior plane of religious devotion”. This is one of a series of acts of the Prophet which indicate the sanctity of religions which preceded Islam. Based on a reading of certain Qur’anic verses on the subjects of salvation, the Umma and religion, the author argues that “the essence of religion is immutable, only its forms vary”. He goes on to state that ”the universal message of the Qur’an invites the Muslim to manifest respect, tolerance and reverence for that same essence which resides at the core of all the revealed religions of mankind”.

How you can Help Ismaili Gnosis Stay Alive and Continue Publishing

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

Acceptance speech, Tutzing Evangelical Academy’s Tolerance Award, Tutzing, Germany, 20 May 2006.

Recital E in the Constitution of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims, dated 13 December 1986, states that the Constitution is intended to be in conformity with ‘the Islamic concepts of unity, brotherhood, justice, tolerance and goodwill’.

Acceptance speech, Tutzing Evangelical Academy’s Tolerance Award, Tutzing, Germany, 20 May 2006.

Address to the Enabling Environment Conference, Kabul, Afghanistan, 4 June 2007.

The Quran stresses that God’s message, though diversely expressed to a plurality of communities during different intervals of history, is universal and perennial, and therefore in accord with the principle that ‘Truth is One’.

In his memoirs, Aga Khan III acknowledges the universality of the divine revelation and the numerous messengers who have conveyed the messages of this revelation, citing ‘all the Prophets of Israel’ as well as ‘similar Divinely-inspired messengers in other countries – Gautama Buddha, Shri Krishna, and Shri Ram in India, Socrates in Greece, the wise men of China, and many other sages and saints among peoples and civilisations of which we have now lost trace.’ The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time (New York, 1954), p. 174.

In this respect, the Quran is analogous to the Christian doctrine of faith and good works – see James 2:17, Matthew 7:20.

Address to the international colloquium ‘Word of God, Art of Man: The Quran and its Creative Expressions’, organised by The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 19 October 2003.

Ibid.

Interview with António Marujo and Faranaz Keshavjee, Paroquias de Portugal, Lisbon, 23 July 2008.

Keynote address to the annual Conference of German Ambassadors, Berlin, 6 September 2004.

Interview with António Marujo and Faranaz Keshavjee, Paroquias de Portugal, Lisbon, 23 July 2008.

The Samuel L. and Elizabeth Jodidi Lecture, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 12 November 2015.

Commencement ceremony, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, New York, 15 May 2006.

The Samuel L. and Elizabeth Jodidi Lecture.

Interviewed in the film An Islamic Conscience: The Aga Khan and the Ismailis, 6 December 2007, dir. Shamir Allibhai, William Cran and Jane Chablani, with consultants Dr Ali Asani and Dr Malise Ruthven, 2007. The film can be found at www.agakhanfilm.org (accessed August 2017). The excerpt is cited by NanoWisdoms (emphasis added).

Tenth annual LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecture, ‘Pluralism’, and conversation with John Ralston Saul, Institute for Canadian Citizenship, Toronto, 15 October 2010.

The Samuel L. and Elizabeth Jodidi Lecture.

Ibid.

Acceptance speech, Tutzing Evangelical Academy’s Tolerance Award, Tutzing, Germany, 20 May 2006.

Tenth annual LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecture.

Acceptance speech, Tutzing Evangelical Academy’s Tolerance Award, Tutzing, Germany, 20 May 2006.

As salamu alaikum ya Ali madad to you dear Imam's mureeds! Make a good publicly available article about Imam Hazrat Abu Talib(Imran)(peace be upon him) and debunking sunni myths about him please